Urban sanitation and gender based violence (GBV)

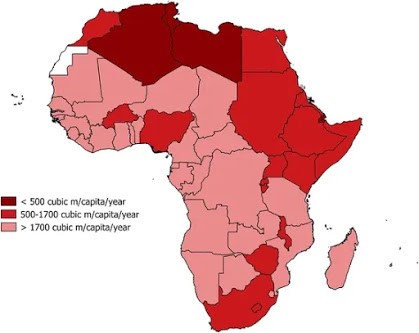

The acceleration of urbanisation will increase pressures on water resources, with Africa being forecasted to experience the most growth ( OECD,2019 ). Poor access to sanitation or water increases the risk of violence for women which also impoverishes their families, communities and societies ( Amnesty,2020 ). This post will unravel the implications of gender based violence (GBV) on women and girls’ abilities to access WASH facilities and initiatives seeking to address this. GBV and WASH in urban informal settlements GBV can significantly impact access to adequate water sanitation and hygiene for women and girls and in some cases boys and men. As the world recently marked world toilet day (Nov 19) it emphasises how without toilets basic hygiene practices are compromised. In Makuu informal settlement in south-east Nairobi Kenya, ‘going to the toilet’ is not just a public health or infrastructural matter but also a matter of personal safety. “Women, more than men, suffer the ind