Water scarcity and groundwater use in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A gendered perspective

This blog will highlight the discrepancies in current ways water

scarcity is measured and highlight how water scarcity is not synonymous to

water access. It will also underline how economic water scarcity facilitates

gender disparities, through the arising inequalities surrounding groundwater

use and access in Ethiopia. Many development goals seek to address water

scarcity as the uneven spatial and temporal distribution of water, combined

with population growth, urbanisation, industrialisation and intensive

agriculture, has resulted in increased pressures on water resources globally

(Demie et al, 2016).

Water Scarcity in Africa

Firstly, the definition of physical water scarcity

and economic scarcity should be distinguished. Whilst the former can be a

result of insufficient water available from the water cycle (Oki,2019), the latter occurs when there is a

lack of access due to the failure of institutions to ensure adequate

infrastructure for a regular supply of water (UNWater,2018).

Africa’s arid climate areas such as southern and

eastern Africa are in the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which

determines the annual seasonality of rainfall. A substantial proportion

(70-90%) of this rainfall is renewed back into the atmosphere through

evapotranspiration (Taylor,2016). This coupled with climate

intensification will exacerbate the physical water scarcity in Africa (UN,2018 ).

|

|

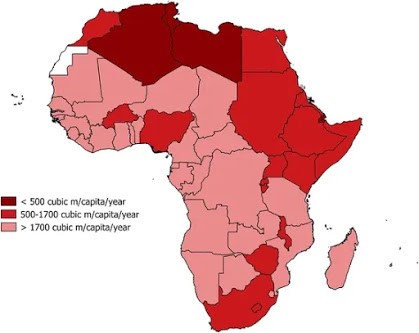

Figure 1: Water scarcity as defined by the water stress index (WSI) source |

|

|

Figure 1 shows that

much of North Africa has a high water stress index (WSI) compared to SSA.

In reality, ‘water-scarce’ countries, such as Egypt and Morocco, report near-universal

(>90%) access to safe drinking water (Damkjaer an

d Taylor, 2017), a

substantially higher proportion compared to SSA (61%) (UN, 2016).

Figure 2: First quantitative map of groundwater storage source |

In addition, the indexes disregard groundwater,

which is a crucial water source in Africa (Figure 2). Its long residence time

means that even in current arid regions, they may still have significant

groundwater reserves. Sahara, for instance, is known to store about 5x105 km3 of water beneath it

(Ward and Robinson, 1989).

Groundwater in Africa: A case study of Ethiopia

All SSA countries - like Ethiopia - have the potential to increase their groundwater usage. However, for this to be done effectively, our understanding of groundwater use must go beyond per household use (Okotto et al, 2015) which inadvertently overlooks gender differences in groundwater use, particularly of women.

|

| Women in Ethiopia fetching water from a borehole source |

Nigussie et al, (2018), monitored groundwater use in two Kebeles (neighbourhoods) in Ethiopia. It was found that women in these regions have high concerns about the use and sustainability of groundwater resources, but are underrepresented in the decision-making process. But why so? Some key points are highlighted below:

1. Women in the Kebeles lack time for

groundwater management, due to the heavy workload from domestic tasks (e.g.

looking after village elders/children and collecting water) and agricultural

tasks.

2. The male dominated culture

discourages women from ascending to positions of power. On average, around 98%

of the water user association (WUA) members in each Kebele are men, despite the

responsibility women hold for irrigation and watering crops.

3. Illiteracy and the resulting lack of confidence impacts willingness of women to participate. Many women in the Kebeles receive shortened education because of the local culture of young marriage.

These points indicate that women’s

participation in the local decision-making process is very limited, and often

they are simply the subjects to change rather than voices in making change.

Their exclusion from technological mechanism training is a key example of this

(Nigussie et al. 2018).

Thus, for more effective groundwater

management improvement on some of the fundamental aspects - like female

illiteracy rates, and access to technological mechanism training - is clearly

required to increase women’s participation.

The next post will further explore the

role of women in water collection, and the wider implications it has to their

lives.

Very good introduction to set out the focus and significance of your post! Great use of resources. I would encourage you to add a few more reflections on how the resources help you to make your point.. You can also do this by adding 1-2 sentences at the end to tie up or summarise your argument.

ReplyDelete(GEOG0036 PGTA)

Very interesting blog post!!

ReplyDeleteThis is interesting how there is actually so much groundwater beneath the continent... I am wondering why are they not being utilised, especially if the water scarcity is so significant in the area?

Is there any effort going in to find out how to utilise these resource in a sustainable way?

Thank you very much! Well despite there being a lot of groundwater present beneath the continent the issues of access are much more complicated! In northern Africa, the overexploitation of groundwater resources has led to a rapid depletion in aquifer levels. So, one of the issues is finding methods to sustainably exploit groundwater in sub-Saharan Africa and then building the infrastructure to distribute and manage the water. While many villages and small towns do have access to groundwater supplies through boreholes and wells one effort to increase groundwater use is by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), who are investing £770m to provide water to 4 million rural households and for sustainable groundwater irrigation for the millions of farmers. This intends to help increase agricultural production output and support local communities.

Delete